Each spring the residents of Devil Lake, both permanent and seasonal, watch the progress of the snow melt and ice breakup, compare the date of the last ice seen on the lake with those of previous years and, occasionally, grouse about high water levels and ice damage. It is not uncommon during this period for one or more docks to become dislodged from their moorings and float freely in the lake. The unusually low water levels of Devil Lake in the fall of 2024 also generated considerable discussion. The purpose of this article is to provide an historical overview of how the water levels in our lake have been controlled, by whom, and to describe some controversies regarding the water levels and the dams that control them.

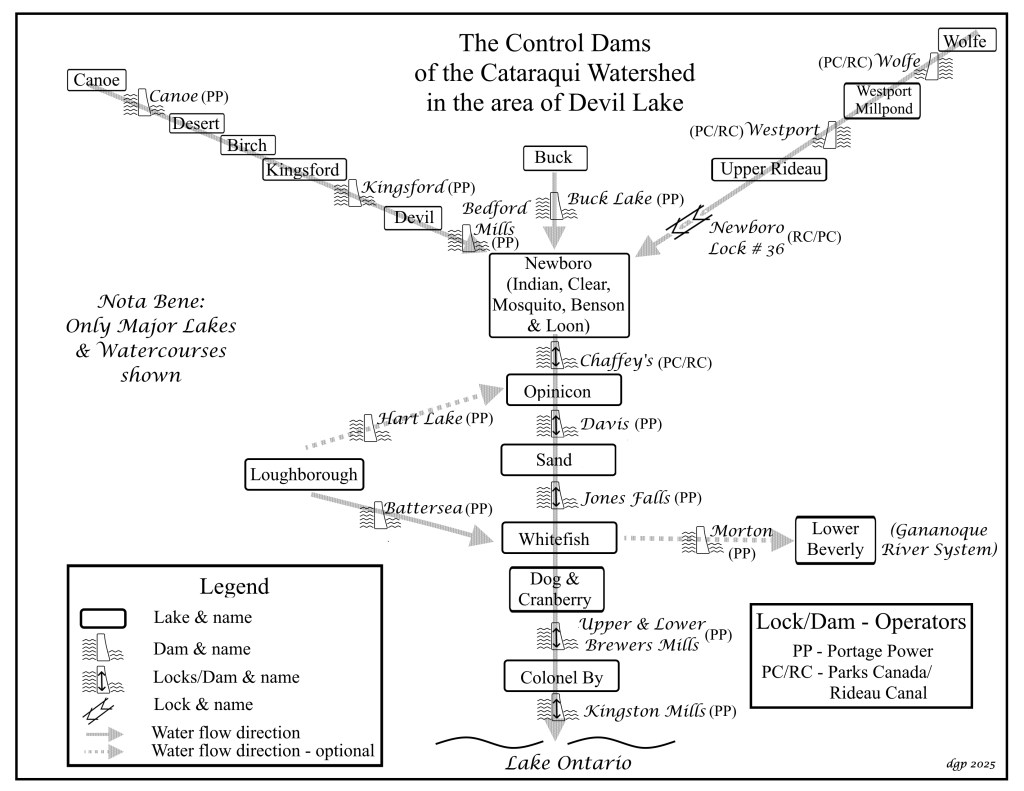

Devil Lake’s water is supplied by several feeder lakes, including Canoe, Desert, Birch, Kingsford, and Christie Lakes, and the water flows out of Devil Lake at its northeastern edge through a steep waterfall (known as “Buttermilk Falls”) into Loon Lake at Bedford Mills. This water catchment area is known as the “Devil Lake watershed” (a watershed is a land area that funnels water to a common body of water, like a river or a lake). There it flows into the southern part of the Rideau Canal watersheds, whose highest point is Upper Rideau Lake. From Upper Rideau, water flows south through the Newboro Lock and north through the Narrows Lock. The southern Rideau watershed is, in turn, part of the Cataraqui River watershed, which ultimately drains into Lake Ontario or the St. Lawrence River. The water level in these lakes is controlled by a series of dams. The lakes and dams of the Cataraqui River watershed are shown in the accompanying schematic.

At present, a variety of agencies, including Portage Power (a subsidiary of Hydro Ottawa), Parks Canada, the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority, the Cataraqui Region Conservation Authority, and the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, all play a role in the control, regulation, and monitoring of the flow of water through the dams in our area. This, however, has not always been the case.

Benjamin Tett Sr. established a sawmill at Bedford Mills in 1831 (see the article https://devillake.org/the-bedford-mills-sawmill/ for more information). Initially, the mill was quite small but, over the next 15 years, it was expanded twice. Each expansion included the construction of larger wooden dams in order to raise the head of pressure of the water, which in turn powered the new saws. The most significant expansion occurred in 1846-47, when a new dam was built higher up in the waterfall at Bedford Mills. This dam raised the level of Devil Lake by about six feet, significantly altering the lake’s topography. Several shallow areas surrounding the lake were flooded, new islands were created, and the northeastern-most end of the lake near Bedford Mills, previously a long narrow stream called “Lock Creek,” was transformed into the deep bay now known as the “Mill Pond.”

Additionally, Tett Sr. constructed wooden dams and timber slides at the outlet of each of the feeder lakes of Devil Lake. These structures helped control fast spring runoff and assisted in the transport of logs which had been sawn during the previous winter. After passing through the dams and slides, the logs were sent down the creeks which flowed from one lake to the next, where they were assembled into raft-like structures (called “booms”), transported to the end of the lake where the boom was disassembled, and the logs were then fed through the next dam and slide. The process was repeated until the logs eventually reached Devil Lake and the sawmill at Bedford Mills (see the article https://devillake.org/cutting-and-transport-of-timber-at-devil-lake/ for more detail).

From 1851 to 1871, Bedford Mills was leased to three Chaffey brothers, George, William, and John; after 1863 it was leased to John Chaffey alone. During this time, the dams and slides were repeatedly rebuilt and improved each winter. Beginning in 1872, the lease for Bedford Mills was transferred to Tett Sr.’s sons, John Poole Tett and Benjamin Tett Jr. Throughout these years, control and maintenance of the dams at the feeder lakes remained solely the responsibility of the mill owner.

Construction of these dams created some problems. During the spring, flooding on lands adjacent to the dammed lakes was not uncommon, raising objections and periodic demands for compensation from landowners and farmers. Additionally, decades of lumbering and agricultural settlement disrupted the natural buffer previously created by the dense forests, leading to excess water runoff from rainfall or melting snow. This in turn caused problems with navigation on the Rideau Canal: during the spring, water levels on the Canal were often too high and, more commonly, in the late summer and fall they were too low due to dry weather conditions. The Devil Lake watershed is the largest reservoir for the southern end of the Rideau Canal waterway, and it drew particular attention whenever Canal navigation was poor.

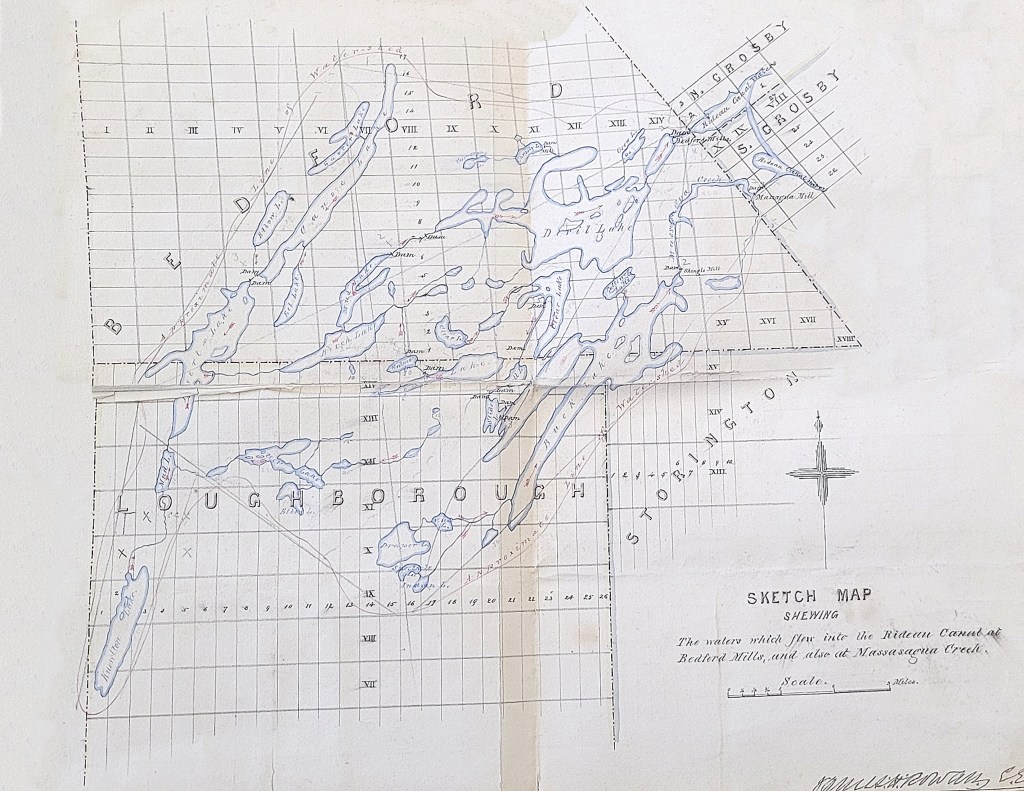

In the mid-1860s, the shortage of water caused so much concern that a Select Committee on Water of the Rideauinvestigated the problem and suggested to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada that there should be more efficient management of the lakes flowing into the waterway. In early 1864, engineer James H. Rowan, at the request of the Department of Public Works, personally visited the area of the lakes in Bedford and Loughborough Townships which drain into the Rideau system at Bedford Mills and nearby Mississauga Creek. His report suggested that it was feasible for the government to build and maintain all necessary reservoir dams. While not fully endorsing Rowan’s suggestion, in the fall of 1865 the government commenced work on improving the water supply to the Rideau Canal. This included the repair of a few reservoir dams, the construction of two new ones, and an attempt to work with the owners of existing dams, such as Benjamin Tett Sr. and John Chaffey, to consider Rideau Canal water requirements and to adopt a mutually agreeable approach to compensation issues.

The dam at the outlet of Kingsford Lake (at the time called Upper or Little Mud Lake) near the head of Devil Lake, was, for many years, the source of considerable flooding in Bedford Township. In a letter written to his member of Parliament, Benjamin Tett Sr. provided a brief history of that particular dam and the changes in water levels which resulted from its construction, which his letter suggested had occurred in about 1846 or earlier. Tett Sr. wrote:

The Dam has been there for 30 years past or more and raises the water in the Creek between Devil Lake and Little Mud Lake about 6 feet, the consequence is that Little Mud Lake is raised about 6 feet, between which the and next Lake above “Birch Lake” there is a fall of about 2 feet, and the Lakes above are consequently only raised say from 10½ inches to 3 to 4 feet, some more some less. The Lakes thus raised are Little Mud Lake, Birch Lake, Desert Lake, Great Mud Lake, Otter Lake, Knowlton Lake, and some other Lakes, embracing together in length from 30 to 40 miles, with a width probably from ½ a mile to 3 miles wide, and enabling the Settlers & Lumberers to bring down Saw Logs and Timber to the Mills & Rideau Canal.[1]

Any compensation paid to settlers because of spring flooding resulting from dams was provided by the mille owners. Partly because they were tired of dealing with such compensation claims from settlers, and partly due to the dwindling supply of suitable timber in the area, John Chaffey and Tett Sr. decided in 1871 to abandon the dam (which they described as “old and worn out”), and the government was notified of their intentions. The following year, the Dominion Government assumed control and rebuilt the dam as a reservoir dam for the Rideau Canal system (the dam then became known as “Chaffey’s Dominion Dam”). After rebuilding the Chaffey Dam, the government suggested it should not assume any liability for compensation at the dams it controlled. This suggestion caused consternation not only among the saw and grist mill owners but also within government circles.

In 1875, the government concluded that it also would abandon the Chaffey Dam and that no further payments for damages would be made – a decision vigorously opposed by Benjamin Tett Sr.’s sons, who by then controlled the water flow through the other dams in the Devil Lake area. In a flurry of correspondence addressed to government officials in the spring of 1876, the Tetts argued that the dam should be maintained and improved, as it was needed as a reservoir for Rideau navigation. They also contended that, if the dam were torn down or continued to deteriorate, the settlers would have no means of bringing out logs cut during the winter, and they would thus lose a valuable source of cash income. In the aforementioned letter, Benjamin Tett Sr. even put forward the following somewhat novel proposition: “[…] it is much to be feared if the dam is taken away the pestilential Air will be so great as to create Fever and Ague, Intermittent and other Fevers to an alarming extent.”

In the summer of 1876 matters finally came to a head. For several years, landowners, who were unhappy with the lack of government oversight and inadequate compensation, had occasionally tampered with the reservoir dams at the feeder lakes. In July 1876, about a dozen farmers, disguised by blackening their faces, took matters into their own hands and destroyed the Chaffey Dam. The incident was widely reported and even reached the House of Commons. David Ford Jones, the Conservative Member of Parliament for South Leeds, described the farmers as a: “band of armed ruffians.”In contrast, Schyler Shibley, the Reform Member for Addington, called them: “aggrieved respectable citizens seeking their rights.” An anonymous note to the Tett brothers, dated August 23, 1876, stated [sic]: “Mr Tate you nead not put a damb there we will tare it away if glycerene quicksilver powder axes or saws etc will do for we are the boys that fears no noise.” The government took no steps to investigate the crime or to repair the dam, which was finally rebuilt by the Tetts several years later.

In 1903, the wooden dam at Bedford Mills was demolished by the Tett brothers and replaced with a cement dam. The new dam was lower in height than the old dam, resulting in a reduction of Devil Lake’s water levels by almost a foot. By the turn of the 20th century, the various industries at Bedford Mills were being operated at a much-reduced capacity due to the declining availability of natural resources, and all were shuttered by the late-1920s. After the closure of the grist mill in 1915, the Tetts decided to establish an entirely new venture by building a hydroelectric power generation plant which harnessed the power of the water flowing from Devil Lake at Bedford Mills. Over the next few years, the plant was expanded, eventually providing power to Newboro and Crosby as well as to farms along the route (see the article https://devillake.org/hydroelectric-power-generation-at-devil-lake/ for more information). The Bedford Mills dam, like with all others in the area, was now being used primarily for power generation and control of Rideau Canal water levels rather than for the exclusive use by mill owners.

In August 1942, the dams and water rights at both Bedford Mills and at the head of Devil Lake were sold for $10,000 by the Tett estate to the Gananoque Electric and Water Supply Company, which operated hydro plants at Gananoque and along the Rideau Canal at Jones Falls, Upper Brewer’s Mills, Washburn (Lower Brewers Mills), and Kingston Mills. The Gananoque company raised the height of the dam at Bedford Mills by one foot, again raising the water level in the lake by approximately that same height. In about 1943, the Gananoque company built new cement dams at Kingsford and Canoe Lakes. These dams also raised the water levels in those lakes, resulting in some flooding for which the company was required to pay compensation for the resulting damage to roads and property. According to residents, the company was less than diligent in controlling the water levels in Devil Lake, with recurring complaints about levels being too high in the spring and too low in the fall. In 1947, several cottagers, including members of the Hayes family (the then-owners of Turnip Island) and the Vanderbilt family, sued for damages to their docks and boathouses. The lawsuit was eventually settled by Belle Hayes in 1950, with the payment of modest compensation as well as an agreement by the Gananoque company to more carefully monitor water levels. More importantly, as part of the settlement agreement, the company undertook to not to raise water levels: “above the top of an iron pin set in the rock near the upper dam at Bedford Mills.”[2] This allowed residents to accurately observe water level themselves.

In December 1948, the Tetts closed their hydro plant at Bedford Mills, and the Hydro-Electric Commission of Ontarioin Toronto (also known as HEPCO and, later, Ontario Hydro) assumed responsibility for the distribution of power in the area. The Gananoque company continued to maintain and manage the dams at Canoe, Kingsford, and Devil Lakes for many years before eventually selling them to Fortis Inc., which, in turn, sold them to the current owners, Portage Power.

The dam at Bedford Mills is a dangerous place, and at least two drownings have occurred there. In June 1837, Edmund Tett, Benjamin Tett Sr.’s younger brother, drowned at the age of 33 while trying to dislodge logs stuck in the timber slide in the waterfall. In July 1986, a 16-year-old boy was fishing from the top of the dam. When his lure became snagged in the bottom of the pond in front of the dam, he dove in and attempted to retrieve it. Unfortunately, he was caught in the powerful current and drowned after being trapped underwater in a logjam at the base of the dam. Following his death, signs warning of the danger of the dam and advising people to stay clear of it were installed.

Careful control of the water levels in Devil Lake should be a concern for all residents. Both high and low water levels can create problems for access to the water by people and watercraft, as well as cause damage to structures such as docks. More importantly, however, they can impact the aquatic ecosystem. High levels in the spring can have adverse effects on several species of wildlife. Ideally, the lake level should be held steady at its low fall level until at least February in order to minimise detrimental consequences for hibernating animals such as beaver and muskrat, whose dens were constructed based on these water levels. Excessively high levels in the spring can also disrupt traditional nesting sites used by loons.

Our lake trout population is currently considered to be healthy, but Devil Lake has been deemed by the Township of South Frontenac to be a highly sensitive environmental area for lake trout. Measures have been recommended to protect the aquatic ecosystem, particularly with respect to lakeshore development and excessive phosphorus which comes from septic systems. In addition to these factors, low water levels are also an important concern for lake trout. They spawn each October on a bed of gravel and rubble, close to the shoreline of the lake and on rocky shoals, at a depth of between one and six metres. Spawning can be affected by both fluctuating water levels and flows, so it is crucial to maintain consistency during the period of spawning, incubating, and hatching. If the water levels are lowered too much during this time, eggs may be killed if exposed to ice or air. In 1991, a working group of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources commissioned the then-definitive study of lake trout in Ontario, and its report contained several recommendations designed to ensure the health of the species. With respect to drawdowns, the report stated: “Ideally, drawdowns should be completed before the start of the lake trout spawning season and overwinter drawdowns should be prohibited. Given the requirement for hydroelectric generation and spring flood control, we recommend that agreements for water drawdowns on lake trout lakes be negotiated to mitigate the impact on spawning shoals.”[3]

The Bedford Mills dam has developed a slow leak, which is not surprising considering its age. This leak led to an unprecedented drawdown of the water levels of Devil Lake in the fall of 2024, which allowed Portage Power to conduct a thorough inspection of the dam. The company commissioned an engineering firm to examine the dam and its rock footings and provide a report on whether the dam should be repaired, replaced, or left alone. As of the date of the writing of this article, the recommendations are not available. Consistent with its objectives, the Devil Lake Association regularly communicates with Portage Power and its members regarding the lake’s water level, and we will advise members of any updated information regarding the state of the dam at Bedford Mills as it becomes available. It is to be hoped that the necessary repairs to the dam, if any, will have a minimal effect on the Devil Lake ecosystem.

-John Gray

May 2025

References:

[1] “B. Tett to D. F. Jones Esq. M.P. Ottawa, March 22, 1876,”, Library and Archives Canada, RG11, B1(a), Vol. 481, Microfilm reel T-901, letter no. 58231, p.000381. Accessed online at https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t901/2132

[2]Personal communication from Michael Payne, President, West Devil Lake Association, February 2025

[3] C. H. Olver et al., Lake Trout in Ontario: Management Strategies, Ministry of Natural Resources, Toronto, ON, 1991, p.44